Curious Roots Episodes

Listen to all episodes of Curious Roots here on our website, Apple, Spotify, Youtube Music, and iHeart Radio.

Season Two

Episode 6: Rich Connections

The second part of our interview with Mr. Griffin Lotson brings us to our final episode of season two. Mr. Lotson continues his story about Kumbaya. Discussed in this episode, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies Among the Georgia Coastal Negroes and its connection to Mr. Lotson’s story about Kumbaya as well as the infamous Old Man Thorpe father to my third great grandmother Ethel “Effie” Proctor. He also shares how he became the manager of the nationally acclaimed Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters.

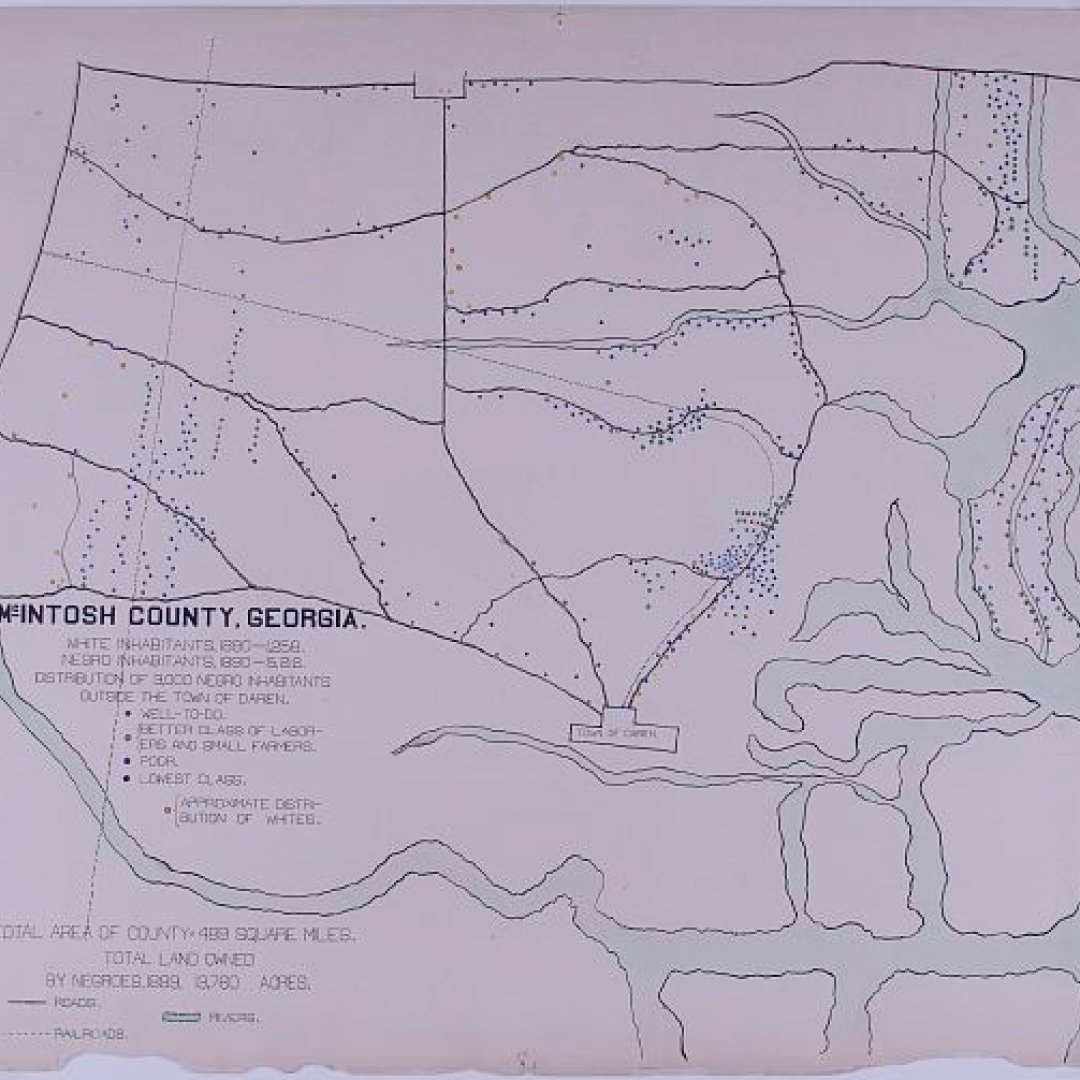

Image: Du Bois, W. E. B. The Georgia Negro Darien, McIntosh Co., Ga. Distribution of Negro inhabitants. Georgia Paris Darien France, ca. 1900. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2013650364/.

-

Archival Audio

Miss Mary Moran: Rayfield's my oldest son.

Michelle McCrary: I knew we were all related somehow.

Margaret Baisden White: You know, that's another thing I never, cause I really

didn't, haven't found out on whose side that Bob and I are related. Whether it

was my grandmother or the Baisdens, you know. Or, or how the, you know, the

Proctors, or Eliza Baisden, Baisden, Uh huh. Okay, so it comes, so I'm related to

the thoughts from the Baisden side then?

Miss Mary Moran: From the Baisdens.

Margaret Baisden White: Okay. Cause I didn't know, I knew it had to be either

Baisdens or Proctors. That's right. And, and Chester? Chester Dunham. Baisden.

I thought, but just seemed like I was leaning towards my mother. My grandma

dad said, which did I come in with? But everybody on Harris neck wasn't really

here. Everybody, everybody was everybody else, you know, because, and

everybody, you know, people are dumbfounded when I said, and Aunt Gladys

was a blood relative.

Yeah. And Uncle Richard was a blood relative. And they said, what did they do?

Married? I said no. And Gladys was my aunt from my father's side. And Uncle

Richard is my uncle from my grandfather's side. Right. So Uncle Richard was

my grandfather, and Gladys was my aunt. That's right. So, I mean, and they look

at me like, um.

I would say it was something else. Yeah, I don't think there was a person out

here that wasn't related to the other person in some way or fashion. But, uh, it

was just. But there was just a whole bunch of, and everybody's a cousin. Yeah,

and everybody was out here together. It was just, there wasn't any outsiders.

Miss Mary Moran: Right. They were among themselves.

Michelle McCrary: Do you remember when the government first came in

here?

Miss Mary Moran: Oh yeah, back in 1942. What'd they tell you? I was 19

years old. What'd they tell you when they first got out here? Well, I remember

this man came by our house, and his name was Bado Dean He was a white

man.

And he had a big paper, and he said that, uh, we had to be out there by, we had

two weeks notice. And we had to be out there by the 27th of, uh, July. Because

they were gonna burn us out. They did burn Evelyn and her mother’s house. By,

you know, by being slow. He just was dumbfounded and didn't give him but two

weeks.

And people had to get all them things together. Evelyn's the one she got, ran on

her mother. Went back in there to get some more things. The chicken was flying

all in the woods, falling from the fire. Yes, they did. Government will offer

nothing and what they did offer was nothing. But they didn't give you time to

leave.

That's right. They didn't give us for seven dollars an acre. Those who got paid.

Those who got paid. Some of them people, like, um, Who was it? Uh, Some of

them were Dunhams. They didn't get no money for it. They lived away. and they

just took it more close. The governor just take it.

Margaret Baisden White:, I know my grandmother, I remember one day she

came over to the house and she said she had to go, come out here. Because she

had to sign some papers to get the few dollars that they were gonna give her for

her mother, her her mother and, and, and father. Yeah. Right. And, and she, um,

she came, I think she came back with a deed. I don't, I don't know, uh, what

happened. But she had, uh, a deed. Because it had, um, her name, and it had my

mother's name.

That was the only place, I think, besides my mother's, um, marriage license and

birth certificate, that had her real name on it. And it had Little Willie's name on

it and I was coming to meet little Willie.

Miss Mary Moran:,He's dead too. Yeah. That was the day of his son. Yeah. Did

you know Cleophus? Cleophus Spencer? Did he live down there? Yeah, yeah,

he lived down there. Yeah, he died a real long time ago.

Michelle McCrary: Welcome to Curious Roots. I'm Michelle McCrary. Before

we hop into the final episode and the second part of our interview with Mr.

Griffin Lotson, I wanted to come back to a thread that I neglected in the

previous episode. When Mr. Lotson was speaking about Kumbaya and the way

that he made the connection to that song, and a man named Henry Wiley, who is

from Darien, Georgia, he mentioned that he listened to the song in a home that

he purchased, which formerly belonged to a Miss Jane.

He said a Miss Jane from Drums and Shadows. Now, Drums and Shadows, if

you don't know, is a book that was done by the Georgia Federal Writers Project

and the full name is Drums and Shadows Survival Studies Among the Georgia

Coastal Negroes. And this book was a huge source for so many researchers and

also many, many writers, specifically Black women writers like Toni Morrison,

um, Polly Marshall.

They found all of this information about Gullah Geechee people from this

Federal Writers Project and they wrote amazing works, um, The most famous

I'm sure you know is Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon and she got inspiration

directly from this book. So That is what Mr. Lotson was talking about. So, of

course, I had to scootaloot over and get my copy I actually have two copies and

I Went into the book and started looking for Miss Jane.

I was like, where is Miss Jane, Miss Jane? And as I was going through the book,

I came to the chapter about Harris Neck. And funny little story about the chapter

on Harris Neck, all my people, most of my people, are in this chapter, including

Um, Isaac Basiden Jr., who is my second great grandfather, I believe, and they

have a description of him, and I'll read a little bit of that for you:

It says, Later that day, we stopped at a neat whitewash cottage and talked for a

while with Isaac Baisden, a blind basket maker about 60 years of age. The old

man had learned his trade in his youth before he had gone blind and now

supported himself comfortably in this manner.

So they talk about, um, speaking to Isaac Baisden and they also talk to, uh, Rosa

Sallins, who was Rosa Baisden, who's also another, uh, relative and ancestor.

And she talks about the fact that she is, uh, kin to Liza Baisden, and Liza

Baisden is Anna Liza Baisden, who married the Queen. Joe Baisden. Joe

Baisden was the son of Mark and Catherine Baisden. And Mark and Catherine

are my fifth great grandparents. And Annaeliza Baisden, Thorpe married Joe

Baisden, so they talked to Annaeliza, and then they also mentioned, um, a

woman called Catherine Baisden.

They refer to her as the late Catherine Baisden, and they talk about her as a

leader in the community, and that is my fifth great grandmother, Catherine

Baisden, and from this book, I found out that she was a midwife and she

brought over a lot of traditional knowledge from West Africa about midwifery

and medicine.

And so. That was a very, very cool, uh, sidetrack to come back to because I, I

haven't, I mentioned this book I think in season one, but I don't think I went into

great detail other than mentioning that Baisden’s were in it, but, um, those are

the Baisdens who are mentioned in it. And there are some other folks in here

that I found in, um, My travels when I got sidetracked, uh, because the first

person they actually talked to when they go to Harris Neck is one Ed Thorpe.

And if you remember from, uh, Our interview with Adolphus Armstrong, and

I've mentioned it many times on this podcast, that my grandmother's great

grandmother, Effie Proctor, was not a Proctor, but a Thorpe. And her dad was

allegedly old man Ed Thorpe. So I'm thinking that in this book, this is who

they're describing.

So I'll read a little bit of that. The first house we stopped at was that of Ed

Thorpe, a familiar and well liked character in the section. A small, neatly

inscribed placard placed near the gate bore the owner's name. The attractive

house was set well back from the road in a large grove of oak trees, a

whitewashed fence Did the property.

The old man who is 83 years old was working in the side yard adjoining the

house. His broad shoulders and his bright alert eyes made him appear to be

much younger than his actual age. He told us proudly that he had lived in this

particular house for 25 years. He apologized because his present circumstances

preventing him from having the house fence repainted.

So playa, playa. Ed Thorpe was a very young 83, um, a young looking 83. So

this, uh, might be Effie's father, um, described here. So, um, Getting back to

Miss Jane and getting back to, uh, the connection that, uh, Mr. Lotson made and

opened up this massive digression on my part. Um, Miss Jane turns out to be

Auntie Jane Lewis, who is in the Darien section of the book. And at the time, in

about 1940, Miss Jane says she's about 115 years old. She shares a story that

she's originally from North Carolina and a man named Robert Toodle who was

a human trafficker who enslaved her and sold her down to Georgia when she

was 21. So she's 21 years old.

She's trafficked. down to Georgia, and she is bought by another enslaver and

trafficker named Hugh, Huger Barrett, and he owned a plantation called

Picayune Plantation. So Miss Jane, uh, that Mr. Lotson refers to, in whose house

he made this connection about Kumbaya. was Miss Jane Lewis of Darien,

Georgia

So I just thought that was such a cool connection and I wanted to share it with

you. And now, since I have digressed very far down the history rabbit hole, I

want to have you enjoy The second half of our interview with Mr. Griffin

Lotson. Thank you so much for listening If you haven't listened to all of season

two, you can now listen to it on the Curious Roots website as well Curious

Roots pod.com All of the episodes for season two have a little player and you

can listen to the episodes right on my website so if you don't do the podcast

player thing or you don't do Apple or Spotify or iHeartRadio. You can listen to

Curious Roots on the website, CuriousRootsPod. com. Thank you again for

listening to Curious Roots.

H. Wylie Singing: Somebody needs you Lord Kambaya. Somebody needs you

Lord Kambaya. Oh Lord Kambaya. I need you Lord Kambaya. And I'll need

you Lord Kambaya. And I need you lord Kambaya Oh, lord Kambaya

Kambaya, Kambaya, Kambaya my lord Kambaya Kambaya my lord Kambaya

Oh, lord Kambaya In the mornin dillard, come by ya, In the mornin mornin

come by ya, In the mornin dillard, come by ya, O Lord, come by ya.

O Lord, come by ya, In the mornin dillard, come by ya, In the mornin dillard,

come by ya.

Griffin Lotson: Come and his words was come by. Yeah. And he said his name,

the Library of Congress, and nobody in the world knew what his name was.

They said H. Wiley. They didn't know where he was from, because they said it

was recorded maybe somewhere near Darien, Georgia. At the end, Robert

Winslow Gordon, uh, the gentleman that recorded and became the folklorist of

the Library of Congress, in my closing with that, he recorded and let him talk,

as he did with some of the other Gullah Geechees and African American, and

say their name and where they're from.

I listened to it. After almost a hundred years, I listened. Ninety years for sure,

and I'm like, I know what his name is. His name is Henry Wiley. I'm Henry

Wiley. I know where he's from, Darien, Georgia. What happened, the mistake

they made, they had their interpreters, but the interpreters did not know the

dialect.

I was birthed a Gullah Geechee. All I did, my claim to fame is, I just listened to

it and I understood the words. Now, I could say things and make it sound

sophisticated, and I did all of this to impress people, but I'd rather tell the truth. I

just listened. And I'm like, his name is Henry Wiley, why they don't have that

written down anywhere?

I Library of Congress don't have it, it's nowhere in the world. They say H.

Wiley, his name is Henry Wiley. He said where he's from, there in Georgia. But

he said it in the dialect, that patois, okay? That Creole. And it was simple, any

other Gullah Geechee could have listened to it. They did not allow any other

Gullah Geechees to listen to it.

Until I got my hands on it. And as they said, arrest, arrest, arrest. is history. Uh,

you can go to Sweden and in the Sweden dialect, I'm interviewing for Sweden.

You can go to London, England. I'm interviewing about the Kumbaya. So it

went worldwide on that history. And I'm grateful that God allowed me. I'm just

hoping someone else can find more information about that song later after my

days are over with.

Michelle McCrary: Thank you. Thank you for your work on that. And, and

thank you for sharing that story. And you mentioned that when the Gullah

Geechee Ring Shouters sang that song, you went viral and got three million hits.

Can you tell folks who may not know a little bit about the tradition of the ring

shout and how you got involved as the manager of the Gullah Geechee Ring

Shouters?

Griffin Lotson: Yes. Okay. I'll start in the beginning. The year was, and I'm

only fuzzy for one reason. I was busy working in my nonprofit because I always

wanted to do humanitarian work. And, uh, we had built our, uh, apartment

complex, uh, there. And, uh, so I was busy taking care of my nonprofit work.

And one of them came, the group came to me and asked me, would I manage a

lady by the name of Miss Marjorie, uh, Washington.

Uh, another lady by the name of, uh, Joanne Wallow, uh, uh, uh, Ross and I

mentioned the Ross and Major Butler, Washington because Major Butler,

Washington is tied into the Butler plantation, which most know as one of the

largest slave trade in America's history. Uh, the Wall Tower came from Liberty

County, from a wall tower plantation, and she did her research.

So they came to me and a few of the other members and asked me would I

manage. I'm extremely busy. Uh, but I love my culture. And I said, well, you

know, I'll try. But anybody that know me, if If I get involved in something, I

kind of go kind of all out. And that's how I got involved with the ring shot is the

year was 2003, 2004.

Uh, I think it was the latter part of 2003 to be more accurate, but of course I did

not know we would go into international back in 2003. So I didn't write the date

down, but I know it was 2003, 2004, that's for sure. Now. I got involved in that.

And of course, I knew a little bit about it because the first person I ever saw

doing the shout was my grandfather, Nelson Sam.

Uh, he was birthed in 18 94 and I saw him shouting in the 19 sixties when I was

young and it fascinated me. What is he doing? Jumping and shouting and

dancing. I didn't understand that. But, uh, that's what he did. And he had a praise

house and saw us on the ground and the old board slapped with the outhouse on

the outside of the church.

So that was my first experience. Then later in life, uh, I got a chance to see the

ring shout. It was only three famous ring shot groups, uh, then and still is now.

You had the Sea Island singers. Uh, they were very famous. And they're the

ones, uh, through Frankie Quimby, I believe it was, that introduced, uh, uh, very

famous, uh, individual that were doing writing and research about the Mcintosh

County Shouters, which was in Bolton area.

And, uh, and from them, members of the Mcintosh County Shouters spinned off

into what we call now the Gullah Geechee Ring Shouters. And all three groups

are well known, carrying on the tradition. My hope is that others will, because

we are getting older now and we're dying off. So I'm hoping other groups, so I

spend a lot of my time training people, New York City.

Florida, uh, can you believe it? The movie roots are trained professional dancers

there. I'm going to California, December or January and training some people

there. So the tradition of the ring shouting, I say this all the time when we

perform about 80 to 85 percent of the time, I say we're the only culture that have

his birth out of something called slavery.

Uh, the. Ring shout was conceived in Africa. And I say it that way because It

was not called ring shout in Africa. It was called by another name. Uh, in the

Caribbean, it's called the big drum dance of music. Uh, in other parts of the

world, the Easter rock, if you go to Louisiana in the Bahamas, it's called the

rush, but here in America from the plantation, it is called the ring shout, but it

was the African tradition Uh, that we turn in that counterclockwise circle, we

brought it to America, and we practice it on the plantation, along with the King's

language now, the English.

So we kept some of our traditions and mingling in with the new church that we

were in, which is the Christian religion. We never abandoned it. Uh, we kept

some of those traditions. So the ring shout was birthed on the plantation. Well,

we do that counterclockwise that special polyrhythmic beat came from Africa,

but we keep that alive and we never change it for love or money.

And that's what I told the movie Roots. I would have worked for free, but they

gave me a lot of money. And I told the director and I said, look, I'm going to be

honest. You might want to hire someone else, sir. If you're going to change that

polyrhythmic beat. And you don't want to do the counterclockwise movement.

Now, keep in mind, I really wanted this job and it was wow. Movie new movies,

right in 2016. And in my closing, I said, well, he might fire me. He didn't, but I

wanted everybody to know from then up until now. I won't sell out my culture,

not for love or money. If you want to know about the ring shout, I can teach

that.

I can give you the history, but don't change it. Once you have learned it, keep

that change. Anything else you want, keep it. If it's all possible. So that's a little

bit about the history of the ring shout again. I can talk another two or three

hours on that.

Michelle McCrary: Thank you. I know you could, and I appreciate all of this

and, and all of this work, because if it wasn't for you, um, you know, and miss

people like you and Mr. Moran, we would not even be able to hang on to this.

And I'm going to say. Let's skip over something because you bring up all of this

culture and you bring up all of these traditions and most folks know traditions,

culture, language are all always tied to um, place and there are a lot of things

happening on Sapelo and on, and St.Helena, uh, where folks Folks in the Gullah

Geechee community are having a real hard time hanging on to their land. Can

you talk a little bit about what's going on and how that connects to, um, sort of

the jeopardy of holding onto these traditions and having places where people

can go and, you know, reconnect with the land and also with these traditions?

Griffin Lotson: Yes, it's, it's a huge struggle, as you said, and right now we're at

a crossroads, uh, when it comes to cultural land, cultural traditions, grateful for

the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Commission, grateful to all of those boots

on the ground that may not be a commissioner as I am, but they're carrying on

the tradition.

Uh, I would say more than I do in certain arenas. Uh, I got my training, uh,

from a Jerome Dixon from, uh, Sapelo. We were at Geechee Gullah, uh, in

Riceboro. And Craig and a few others, uh, master, uh, basket makers. Now,

Yvonne Grosvenor from, uh, Sapelo Island, uh, area, Bolden area, master basket

making. I got her basket.

On the presidential float because I was on the commission. So I'm in a position

of power to request and get some of our art and culture on the presidential float

for president Obama, first inauguration. We did that. Uh, so, uh, the land, if we

do not have the land, we cannot carry on these traditions. Uh, and people are

moving away.

Uh, I moved away because you couldn't get jobs. And of course, if I move the

way, uh, even if my parents had land, they want to give most people, once they

move away, a lot of them don't want to come back. I'm a little above average. I

came back long before retirement age. Thank God I survived. So you have a lot

of that.

And a lot of those individuals that live in these communities and on these

islands, they move away because of lack of, uh, income. And, uh, once they

move on after so many decades. difficult. I'll start from within and then I'll go to

the without. Um, I used this phrase and did not know a opera would come out of

it.

I met with some individuals. I didn't even know they were that important. Uh,

one was a, uh, Pulitzer Prize poet. Uh, also wind up being the, um, poet Lord of

the United States of America. Uh, Tracy K Smith, uh, and orchestra director, uh,

the president of the Ohio. Uh, uh, symphony, uh, uh, uh, where they, where they

have these things at.

Uh, and, uh, I just talked with them and I gave this scenario and I'm going to

say it to you. Uh, what are you going to do? You live in New York city. You're

four months behind in your house notes. How's no so expensive up there. Okay.

Uh, it's tens of thousands of dollars. Uh, your child's been in school for four

years, getting ready and more because they're getting ready to get their

doctorate.

You'll spend most of your money trying to help your child to graduate from

college because a lot of parents did not graduate from college, but they want

their children to graduate. So you did all the right things. And they are 80, 000

behind in their tuition. You have 15, 000 behind in your house. Note, you have

four acres of land on Sapelo or where I live in Darien, Georgia, that's worth a

King's ransom.

What are you going to do? We all know the answer to that. You have four acres.

You don't live there. You don't need it immediately right now. All four acres.

You're going to sell at least one acre so your child can graduate with their

doctorate to go to be successful. You're going to save your house in New York

because you've got about a quarter of a million dollars plus in equity in that

house.

Now the reason why it's easy for you to sell it now, I talk too emotional with

this, that land that one acre is, you didn't buy it in the first place. You're Your

parents didn't buy it. Your great grandparents or your great grandparents

purchased it. So you don't have the same thought there. He didn't pay anything

for it.

Why am I keeping this? And I'm about to be evicted and my child would not

graduate. Those are tough decisions, tough decisions. And from that phrase,

they actually did an opera. And my mind went blank a little bit, but it was the

Cincinnati Opera House, the director. And they took that story. and made an

opera out of it.

I traveled there to see that opera and wow, did not know it was going to turn

into a life changing thing where other people outside of the Gullah Geechee

culture were saying, wow, we never knew about this culture. We never knew

about things like this, this happening. So we're broadening it. So yes, it is tough.

Now the other half of that, and I'd say a little bit quicker, cause I'm too

emotional with this is the fact that, Hey. Most people in America wants to make

money. That's why we went to college. That's why we, uh, train. Uh, that's why

we get up and go to work every day. We do it for the money. Uh, yes, you and I,

we doing this podcast for the love of it.

You know, we don't get rich off of it. We're doing it for the love of it. And the

last time I checked my salary for doing this podcast is zero dollars because I

love it. As a consultant, I get paid $200 an hour plus. Okay. Sometime it's a

thousand dollars or $2,000 a day, that's what I get paid. But this is love.

So, uh, doing this cast, but people work for money. So the land people that

wants to buy the land, they want a beautiful place to live and they also want to

buy a place that they can make money off of. And then you have the developers,

they're in it to do the same thing we want to do, which is make a lot of money.

And then be able to either keep the land we got a buy more or leave it as I do for

my children and grandchildren. So there's the dilemma. There's the pool and the

pool is tremendous. It is tremendous. You want to hold on to it, but you hadn't

been taught how to keep it. The other guy just want to get it so he can make

money.

He wants to develop. It's tough. We don't have all of the answers. Uh, but we are

working on those answers, how the taxation won't be so high, like Sapelo and

where I live, uh, taxation have went up 100, 200, 300. I know on Sapelo, I've

seen it went up 800%. Who can afford to do that? 100%. So it is a dilemma. We

have to keep fighting.

We have to come up with new solutions. And I think some of those new

solutions are. On the horizon, changing some of the laws. Of course, it's one of

the things that need to be done in my legislative position. We can raise taxes in

the city of Darren and hear me out and I close on it to let you know legislators

could do things.

People of power can do things right now where I sit. All I need is two more

votes on City Council and I can raise the taxes 500%. But guess what? I can

reduce the taxes 500%. And what I mean, reduce it 500%, whatever you're

paying now, uh, we can even eliminate taxes if we choose to. That sounds

fascinating.

That sounds like that's unreal. Of course, either one you do, you'll probably be

voted out of office, but sometime you might have to make some sacrifices as

presidents have done, as legislators have done, And just good people make the

sacrifice. You are making a sacrifice for this podcast that we hope that many

people will view and help change their mind to support the Gullah Geechee

culture and other people that say, look, I'm a judge, I'm a lawyer.

You guys need to make this phone call. And that's what happened to me in my

life for doing interviews like this. Somebody would say, you have your, I'll try

this out. Not to know. We didn't know about it. This is what you can do. And

that's what I have done. They help a lot of communities. They didn't have the

knowledge.

I use my consultant skills and they say, wow, that's a miracle. No, I just gained

the knowledge and I'm passing it on to you. And I'm not charging you a

gazillion dollars. I charged the next person that's trying to disuse me to get what

they want. I charged them the real fee. So I say that to say this, it is a struggle.

But there are solutions. And right now there are some court hearings that's

coming up. There are some petitions to reverse some of the laws. And there's a

lot of people crying up, standing up. And a lot of celebrities are stepping in now

and giving some of those millions that they have, which most foundations, most

people don't know.

And I'm hoping the foundation person will listen in every foundation have to

give away 5 percent of their money. Doesn't matter who they give it to, but they

have to give away 5 percent to a legitimate cause. So when you see people

giving things away, they're actually saving themselves money too with those

foundations because you have to spend 35 percent of your, uh, uh, 100 million.

Uh, so you got to give away about 30 million out of the 100 million. So you put

it in a foundation and a miracle happened. Now that same 100 million, and

there's plenty of rich folks out there today, It's over a billion dollar lottery out

there. Somebody's going to win it. Uh, if you do a foundation, you only have to

give away 5 percent and you can take that other 30 percent and do for yourself.

Or maybe help somebody out on Sapelo or Darien that's about to lose their land.

Thank you. And thank you for that compassionate framing, um, of the choices

that people have. Um, it's a miracle that all of us are here. But I think it's a

special miracle that Black folks and Indigenous folks are here. And there's a lot.

That our culture has had to, you know, survive and holding on to the land, in my

opinion, is just a continuation of that, um,

push to survive and thrive, and I think without the land, that gets really hard to

do. Can I add one thing, just one thing now? No, and it's, I know of some

developers where I used to go, uh, fishing and and crabbing and uh, we would

walk a mile or two just on the banks of the shores and I think it's called a

thicket.

And I was like, wow, there's a multimillion dollar development now. And I said,

I never knew some of these things were back there. And, uh, now they've got

houses all up in there. I used to come back as a boy, it was all woods, but guess

what? Some of the developers do have a heart about culture. Most of them

don't, but there is one structure in McIntosh County where I used to run as a boy

and the former enslaved buildings.

That they used to make the sugar cane where they lived is still there. Now it's

their land. They purchased it outright. They could have came in and just

bulldoze it down and build about three or 4 million homes. Guess what? It's

been there now for over a decade since the development was there two or three

decades now, because I remember when they started building, uh, the latter half

of the last century.

Now we're 23 years in a new century. Wow. And guess what? Those structures

are still there. Family and friends. I take them by to see the tabby buildings that

they're there. So I say that to say this, cause I don't know who I was going to be

viewing your podcast. They may not all be rich, but they may have rich friends.

Uh, my position I'm in now, I've got friends that are rich. Okay. They, they have

millions of dollars. I also have friends that are dirt poor, and I'm glad that my

culture have not changed me in my position that only deal with the aristocrats. I

deal with every spectrum from high to low, the government officials, that's

where I'll be going next week to their parliament and be before them then I

come back and be there with individuals just making sweetgrass basket for the

culture.

Uh, the total spectrum. So, uh, whoever's on this podcast, uh, you might be of

some wealth, help these cultures get to their next level. I'm doing it at my level.

Perhaps you can do it at your level also. Thank you.

Michelle McCrary: And just to, you know, keep pushing a little on that point,

what would be lost if, you know, God forbid. Everybody lost their land and they

just started throwing up, you know, fancy golf communities and expensive

mansions. And, you know, just completely erased all traces of Gullah Geechee

folk from these areas. And I know it's happened. It happened to my family in

Harrison. Um, and it's happened to a lot of communities.

If it continues to happen and people. are not able and they don't have the help to

hold onto their land. Can you just explain the loss for people so they just

understand a little bit?

Griffin Lotson: Uh, yes. I think the most famous one in America was the

Native Americans. They had it. They owned it all. And because of Europeans, as

we call them in our culture, as you say, Harris, Nick area, and where I'm from

Darien, McInnes County, Crescent area, we call them the buckras, which is

white individuals, a term that's used as, uh, uh, yeah, you made the money, but

what have you lost?

I'll use some names and I've never met the gentleman don't know him

personally, but they're a person of wealth. Uh, Ted Turner, he took his millions

and millions and millions. and decide to preserve land his money. But he

decided, I don't want a resort where I can make millions and millions more. Uh,

we need to preserve some of the culture, some of the land, some of the history.

And I'm so glad that we do have the preservationists. I'm one of them. But I'm

also believe in economic development because If you don't have, uh, the

economics, if you don't have the money, uh, you won't be able to keep the land.

Uh, you won't be able to do things you need to do to keep it alive, setting up a

tourist attraction that's owned by the Gullah Geechee's African American.

My wish and hope for Harris neck when they get that land back, uh, that they're

going to have to set up revenue, uh, uh, uh, efforts. I have proven that I've had

more workshop, national workshop. We started with, I didn't even know what a

501 C3 was, and I've raised millions of dollars, built two multimillion dollar

development.

Can you believe that a funny talking? Come you had this show that day, have

our own management company. One of the few that's owned by Gullah beaches

in Southeast Georgia. You make the sacrifices, but it's a cash cow. It produces

money. It produces the milk. Uh, you can't kill all the cows and expect to have a

cow farm.

Okay. And that's what we have to do on our end. And sometime you're going to

need. People don't know in certain communities. They call it redlining. I had to

learn that from hanging out with some of my banker friends and folks that don't

look like me to learn the techniques that are being used. Redlining is simply that

anybody in certain communities will not get money from the bank.

And if you don't get money from the bank, and your cousins don't have can't

lend you any money. Then pretty soon you're going to have to do what? Sell

some land. People have gotten their children out of jail by selling land because

they didn't have the income. So we have to train our children, uh, individuals.

We have to train our grandchildren. In my case, in my, my children to hold on to

a dollar. And I have to set the example first. And I've done that so they can

know you don't have to spend it all. I don't need a Lamborghini. Okay, but I can

do this and I don't have to sell the ancestral land. Okay, I can hold on to it.

I've got ancestral land. I get a letter almost every month for somebody wanting

to buy. I'd like to have that money too. But I'm in a position. I don't have to sell.

Okay, I'm not four months behind in my mortgage. I don't have any Children

that's going to get kicked out of college because they can't pay their tuition.

So we have to start training now this generation and the next generation how to

do our part. Uh, well, once was a guy, Kevin Rolock. I think they said in D. C.

No one can save us for us. But us I just like to add on to that. Uh, my uncle used

to tell me it's good to know poor folks, but for God's sakes, don't know all poor

folks.

Now, most people think that's my phrase. Uh, but I got it from him and they

said, I like what you're saying, man. It's good to know poor folks, but don't

know all poor folks. I'm on almost first name basis with legislators. I've met

personally, at least three to four presidents. I put myself in those circles.

Okay. Bankers that know me by face and name, you have to learn these traits to

get to the next level. And people like you and I, we just need to train them and

let them know that these are the ways that you get to the next level, not just for

yourself, but for your community, your community.

Michelle McCrary: for sharing that and thank you again for your work. Um,

and everything that you've done for the culture and for the community. And

before I let you go, I want you to tell us, um, where you'll be next. I know you

mentioned you're going to Barbados. So if you want to talk a little bit about that,

um, if you are on social media or anything like that, let the people know where

they can find you.

Griffin Lotson: Okay. Yes. Right now. Uh, wow. Uh, we just did a production,

uh, with the discovery channel, their producers out of London, England. Uh, if

you go to discovery channel and look up hidden America, uh, Butler Island, uh,

some people have already found it. They have over 400, um, million possible

viewers worldwide. So we feel very proud that they did a full production on

that.

So you should be able to find that there. And when we open the museum,

hopefully on the Butler plantation, we're going to make sure, hopefully we'll

make sure that that's one of the sit downs that people can view because they did

hire professionals in and put it together and took them about a year. And they

just released that.

Uh, yes, we will be at the headquarters, believe it or not, of the Gullah Geechee

Cultural Heritage Commission in, uh, Beaufort, South Carolina. This Saturday,

they have a full day of event, I think starting at about 10 that morning to 3 or 4

that afternoon. So not only will the Gullah Geechee Ring Charters be there, A

host of other individuals as carrying on the culture, some of the commissioners,

the full staff will be there.

And if you want to learn more about it, uh, help the commission or the

commission can help you will be in rare form there in Buford, uh, South

Carolina. Just remember Gullah Geechee cultural heritage commission, Buford,

South Carolina, and you punch that in on the internet, you should be able to, uh,

pull.

That up the Barbados is something I've personally been working on since 2011.

When I got elected and then appointed by the president at the time, uh, president

Barack Obama, and just for knowledge, every president have to okay, each

commissioner, I really don't know why I'm still on it because all the

commissioners that were on it, uh, 10 years ago, 12 years ago, when it got

started in 2006, all of them are gone.

I've got 10 consecutive years in. Uh, this make my 11th consecutive years as a

full, um, commissioner. So why I can't figure it out. I think it's because I talk

funny of something, but they kept me on through three presidents. So. First

Barack Obama, then President Donald Trump, and now President, uh uh, Joe

Biden.

I've served under all three of them, and they can put you on and take you off all

of 'em. Okay, me. So come down to the commission. That's, that's on this

Saturday. And then hopefully December, well, I'll be in Atlanta, Georgia.

Atlanta, Georgia, Emory University, uh, Charmaine Manfield. Remember that?

Emory University, Charmaine Manfield will be teaching and lecturing there,

teaching the ring shout and what it's the soul of the ring shot.

Anybody can jump around, but the soul and the meaning and how it got started,

uh, we teach that as we did with the movie Roots. They're professional dancers,

but I had to tell him you can never do the ring shot if you don't know the soul of

it. So we teach that as much as we can to get in the hearts of mind about that.

And that'll be at the Emory University. There's a Praise House there. And I had

it built and Shami and Manfield doing a magnificent job. This month, also, we

have an article coming out in the New York Times. Can you believe that?

Working with the Praise House and the Ring Shout. And I think Atlanta

Constitution is doing something now too with the ring shout.

I just received a call from a friend of mine, um, uh, from Atlanta Constitution,

Ms. Poole. Uh, she just called today, uh, just before I got on this podcast. So

there's a lot more. I don't have time to say them all, but that's just some right off

Of the top that I can mention. Thank you so much again.

Michelle McCrary: And, uh, some of this, because like I said, it's timely, I'm

going to post it on my Instagram, these dates that are coming up. And, um, like I

told you, this will be up in the new year, but. Thank you again. Thank you for

all your work. Thank you for this time. I hope that I can grab you again for

some time. I hope I get to see you in person. Uh, I need to make my way back

down to Georgia to see family.

Um, I'm overdue for a trip. Uh, we haven't been there since, uh, last year, last

April was the last time we were there.

Griffin Lotson: So where are you from? Where do you live?

Michelle McCrary: I live in the Pacific Northwest now. But, uh, I'm originally

from Queens, New York, because my mom moved up from Savannah to

Brooklyn, and I was born in New York, where she met my dad.

Griffin Lotson: Okay. Yeah. I just, I just did the Apollo, but that was last year

and I'm doing another trip there, and we taught. Uh, them, the ring shout also,

and we had a chance to grandstand a little bit at the Apollo theater. That was

wonderful. They did a tribute to the ring shout, the sonic of the ring shout. And

it was marvelous and invited me, uh, on stage.

And that was, that was a treat also. So New York, I'm looking to be back there

real soon.

Michelle McCrary: Yeah. That's my old neighborhood. Yes. Well, thank you

again, Mr. Lotson.

Thank you so much for listening to Curious Roots. Learn more about Harris

neck at Harris net land trust. org. And find out more about their work with the

African American Redress Network at redressnetwork. org. Learn more about

Black coastal communities from North Carolina to Florida at

gullahgeecheecorridor.org. You can support Gullah Geechee communities on St.

Helena and Sapelo Islands by following Protect St. Helena at protectstnhelena.

com. And saving our legacy ourselves, solo at saving our legacy ourself.org. All

links are in our show notes. Thank you to my relatives who are now with the

ancestors, Ms.

Mary Moran cousin Evelyn Greer cousin Bob Thorpe, cousin Chester Dunham.

My father, Rodney Clark, my grandfather, Rufus White and my grandmother.

Season 2 of Curious Roots is produced by Moonshadow Productions, and with

the generous support of Converge Collaborative. Thank you so much for

listening.

Season Two

Episode 5: Rich Connections

Rounding out the final two part episode of season two, is Mr. Griffin Lotson, Georgia Commission Vice Chair for the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission,Chief Executive Officer of the non-profit Sams Memorial Community Economic Development, Inc., and manager of the nationally acclaimed Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters. I sat down with Mr. Lotson last year to discuss his own deep roots in McIntosh County, Georgia heritage and his work to share Gullah Geechee culture globally. He talks about being a part of the beginnings of the creation of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission and how this culture work brought him to share the true story of the famous folk song Kumbaya.

-

Archival Audio

Margaret Baisden White: He used to spend the summers out here with Papa. So, and I didn't know him either. Oh yeah? No, but see he stayed out here and I was in the city. And the only times I came was during the summer and a lot of times he was either in the river or wherever he was. Uh huh. So I really, I seen him a quite a, you know I had seen him a quite a few times but I didn't know him.

Didn't know him at all. Yeah. And if Willie hadn't been coming and spending the summers out here with him, he wouldn't have known him either.

Uh huh. Because

Mama leaves him there in the city. And, and, uh, That's Effie.

Miss Mary Moran: Because Effie was your grandmother. Yeah. And, uh, she was married to Willis Hammonds. Yeah.

Margaret Baisden White: And see, I didn't know Papa. Because he stayed out here. Right. Well, but, uh, People died young. Shelby, um, Mama was sixty, had

it been sixty eight, sixty nine or something like that. Uh, uh, Maddie. No, my mother died three weeks ago. Before she was forty, before her forty fourth birthday. And her name was Mattie. Well, well, well. And Effie was her mother. Yeah, and she, I think she died when she was sixty eight or sixty nine.

Miss Mary Moran: Yeah, them people died young.

I'm older than my mother was. When she died she was seventy five. Yeah, well I'm older than both Mama and Daddy when they died. Mm hmm. She had just turned seventy five. Twelfth of December. She died. I justreached my seventy eighth. I’ll be seventy nine.

Margaret Baisden White: What's your name?

Miss Mary Moran: Mary. They call me Culey. Mama give me that little name, Culey. Oh, I'm Culey. Yeah, I've heard them talk about Culey. Culey, Culey, Culey. I was mama's only child. Culey. But my real name was Mary. Mary Ellen. Oh,you wouldn't believe it I had. thirteen children. I seven still living. Sweet! So and the grandchildren and the great grand when they have that

Michelle McCrary: Welcome to Curious Roots. I'm Michelle McCrary. I am so excited to share the first half of our final episode featuring my interview with Mr. Griffin Lotson. Mr. Lotson is the Georgia Commission Vice Chair for the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor Commission. Chief Executive Officer of the non profit Sam's Memorial Community Economic Mint, Incorporated, and Manager of the internationally acclaimed Gullah Geechee Ring Shouters.

Mr. Lotson’s work and his travels have brought the Gullah Geechee community to folks all over the world. He's done consulting for movies and television related to the culture, and he had a really, really huge part in unlocking the connection of a famous folk song to Gullah Geechee, uh, communities in McIntosh County.

So, I, I don't want to take up too much time telling you what a G he is, um, but you'll hear it when you listen to him talk. I appreciate his support. Time. Um, he's a busy, busy man and he is always all over doing many, many things for the community. So I hope you enjoy this, uh, talk with Mr. Griffin Lotson. Oh, and I almost forgot one more thing.

Mr. Lotson at the time I spoke to him last year was Mayor Pro temp of. Darien, the city of Darien in McIntosh County. So he truly, truly is a force. He's a G. We so appreciate everything that he does for, uh, Gullah Geechee people. And I hope you enjoy this interview. Thank you so much again for listening.

Michelle McCrary:Thank you again for being here. And I like to start off. These questions for my guests with who are you and who are your people

Griffin Lotson: Thank you. My name is Griffin Lotson. I'm a seventh generation Gullah Geechee and will explain some of that as we do this podcast. I hail from Crescent, Georgia, where I was born in the early 1950s, To be, uh, correct and did a lot of, um, ancestral tracing my roots, uh, even back to enslaved, uh, times as we call it.

And, uh, lives in the state of Georgia. They say we talk funny like we're from the islands, man, you know, or we say things like come Yuh dis yuh that day, which is the Gullah Geechee dialect. And it's just a language that's kind of a melting pot of the English. Uh, we learned from what we have, uh, back in time, the slave masters.

And then my, um, uh, in laws, uh, uh, up until today, we just carried it on to the next generation. I try to change it a little bit for my children and my grandchildren, they talk much different than I do, I wouldn't say better, when you use the word better in the Gullah Geechee culture, that means that your language is not good, or your dialect is not good.

And, uh, it's perfect now. But it took me years to realize how perfect it is. So I'll stop there.

Michelle McCrary: Hmm. Thank you for that. And, and thank you for sharing a little bit about the language and the language. I always feel like I need to learn how to speak Geechee. My Aunt Gladys Hayes was the last person in our family to speak it.

So I know, like, Little words here and there, and I can understand when folks speak to me, but I can't speak it. So I've been really thinking long and hard about what I'm going to do about that, especially for my kids. But I can also understand, um, speaking like, uh, of people from the islands, I can also really understand Jamaican Patois, and I don't know that at all, but there's something to it that sounds very familiar to me.

Yeah. Yeah. So thank you for that. And I'm going to jump around a little. I know I sent you some questions, but I have a ton of them, but I want to follow that question up, um, and ask you a little bit about where you grew up. And also, um, if in your travels, you knew people from Harris Neck.

Griffin Lotson: Yes, as I said, I grew up in McIntosh County and, uh, Harris neck is in McIntosh County.

And I love to say this whenever I do lectures. I just did one at a national conference in Florida. And, uh, I say it all over the country. And even when I traveled to foreign soils like Africa, I'll be in the Caribbean next week. I'm very excited about that because Transcribed Uh, we are connecting with a memorandum of understanding, uh, in the Caribbean in Barbados.

So we have a kind of a partnership. So I'm very excited. I push for that, being the vice chairman of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage. Commission, which was authorized by Congress, and so we're in full operation. But yes, Harris Neck is, uh, definitely a part of, uh, my own culture. I use this phrase, and allow me to say this a little bit, uh, dramatizing it, uh, for the effect.

Uh, there's James Napoleon Rogers, which was born into enslavement, and he lived in Harris Neck, Georgia. He had a son by the name of James Monkey, uh, Rogers. Uh, he was not born into enslavement, but his father did. And the monkey Rogers is what we call nickname. Uh, but they call it basket names, uh, back in the day.

So you have James Napoleon Rogers. Then you have James Rogers, his son. And then James Rogers son, uh, name was Leon Rogers. And Leon Rogers had a nephew by the name of Griffin Latsin, which is doing this podcast now. So yes, I have a lot of rich connections to the Harris neck community, including the very, very famous song.

Woka Mona. Kum ba a la lei, uh, James Rogers sung this song. Also, uh, most people don't know that Liberty County. And Macintosh County was one county at one time back in the 1700s and the later part of that, then it broke off into two counties. So all of this is recorded. I'm kind of a geek in the history of my culture.

So I study a lot. I travel a lot, different parts of the world from Africa back to America. So I've done an extensive research. On my own heritage and my own connection going back seven generations. Thank you.

Michelle McCrary: Can you talk a little bit more about, um, what you learned about your family history and about, um, McIntosh County?

Griffin Lotson: Yeah, the one I've been saying the most, I'm going to say now, whoo, 50 plus years. Uh, first heard it and then psychologically. I always remember that and that's why I say I'm proud of my culture now because it once was a time I was not proud of it. And I said this in West Africa and, uh, to a friend of mine that we, he was living over there at the time, Joe Apollo.

And, uh, he is the gentleman that did the work on the research of the, uh, Mende song that we all know. That Amelia Dawley sung in America, and also the African, West African, that Bindu Japati, that sung it in Africa. But we met at the National Theater in Sierra Leone, not theater, but a museum. And I give this phrase, BBC News was there, but I do this at all media.

So I'm going to do it in this podcast now. And, uh, they would say this to me, Boy yuh too Geechee, uh, which hearing it at first is very difficult. But simply, they said, boy, you are too kitschy. Now, what they meant by that, they were saying, young man, you're getting older and you need to move away from your cultural heritage.

Um, now, they didn't say the words that I just said then, and they certainly wasn't saying you need to lose your culture. They knew they were wrong. I would grow up. They knew if I'm going to do better in society, you need to start practicing what we call the buckra or the American way of speaking proper English.

Okay. And, uh, I kept that up until I became a young adult. So everywhere I went, when I left home at the age of 18, 19 years to go to Washington DC, which I lived there for 12 years. I tell people I went through the ritual of making up a language, so my Gullah Geechee would always come out and I would say, Umma, which I should be saying, I am, but I would say, Umma gonna, which I should be saying, I am going to, it would always slip out and I'll try to cover it up.

Most people didn't know what I was doing was covering it up. If I say, you know, I'm a goner, then I instantly, right after I say that, which takes less than one second, I would switch and say, I'm a goner. I am going to the store and opposed to say, I'm going to go to the store. Uh, I hear it. Then I would switch it.

Then I learned to sing my words. I had relatives, which were Gullah Geechees, uh, that lived in New York. So they, they picked up that. New York twang, that New York accent. So I just learned to sing my words and doing this podcast, I would say words similar to this, uh, to make people think that I was refined and not of my Gullah Geechee heritage, and I would just make these fake languages up to impress people.

Or to make them think that I'm not Gullah Geechee. Now, was that a bad thing to do? At the time, I didn't think so because in Washington, DC, folks couldn't understand my dialect. Wherein you couldn't get a very good job, you know, talking to individuals, legislators, or even in business, uh, it would be difficult.

So I did that for a number of years. And then I changed and started learning about my own culture. And who would have ever thought for me the hunger of learning about my culture. And I might've had this, whether you love him or hate him. I like using him because everybody knows about him. Clarence Thomas, uh, Supreme court justice.

He's only about five or six years old and I am, and I started listening to other individuals. And I found out that I wasn't isolated. Uh, just about everybody in the Gullah and the Geechee culture, uh, tried to hide or run away from their own culture. When they were young and all of my great heroes, like Dr.

Emory Campbell, I call him the godfather of the Gullah Geechee, uh, culture. And, uh, people like Supreme court justice, Clarence Thomas, they started saying, well, you know, it wasn't good to be Gullah Geechee back in the day, now, both of them honor their culture and I certainly honor mine. So that's a little bit of, uh, of my background and I can give another two hours on my history of being a Gullah Geechee.

Well, that just means we're going to have to have you come back and just let, and let you rip. So, um, yes, a lot of people don't know about Clarence Thomas, who is from pinpoint, Georgia. He is a controversial figure. Um, but you know, I know that my grandmother would say we're all God's children and I'm going to leave it at that.

So, and I would say, I would say controversial. So. To some, and the most controversial person I know is Jesus Christ. Some love him and some don't. And most politicians are controversial. I tell everybody, every president have about 50 million people that don't like them. I don't know if I know that. Uh, because 50 million people voted for them.

51 million may have voted for them, but 50 million did not, especially the one that lost. So, I just wanted to add that little piece in there, because a lot of people do love, uh, Clarence Thomas. And as you said, he is controversial, uh, to many, many individuals.

Michelle McCrary: Absolutely. And speaking of politicians, you are the mayor pro tem of Darien. And you also, um, work very closely with the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor. Can you tell me, uh, both, about both those states, um, and how, if at all, they're connected?

Griffin Lotson: Yes, both is connected. And, uh, many years ago I set a goal in my life and I was able to accomplish them. A lot of times you don't accomplish your goals.

So I often say if I left today, I would have accomplished most of. of my goals. A lot of failures in the middle because a lot of young people want to hit his podcast and usually with no success. Uh, you don't have failure first. I want to encourage them because you feel and something never give up, never quit is my philosophy.

But yes, uh, besides my religious work, uh, I love doing humanitarian efforts. I always wanted to do that, and I did it in Washington, D. C. as a Gullah Geechee, and I brought that back, uh, to Georgia. I moved back in 1985, and still live here, plan to die here. Uh, yes, I wanted to work in the city, uh, just, you know, setting the pace for the city, and wound up running for office, uh, lost a lot of elections, but now I serve as the second highest position in the city of Darren, Georgia, as the Gullah Geechee.

Uh, mayor pro temp. Ironically, I also serve in the second highest position in the United States of America. I am the vice chairman of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission. I usually tell people Niagara Falls, which about a billion people know about, definitely millions travel there. We have the same designation from the federal government as Niagara Falls.

Thank you very much. We're just not as popular yet as Niagara Falls, but we're moving up that chain very, very, very fast, very, very fast, I should say, and we're, we're proud of it that now many are owning the culture instead of shunting it away.

Michelle McCrary: And, and I thank you for mentioning that. And I don't know, people will know from the intro that you are a big deal.

But you are very much a big deal, and, um, I thank you for your work with the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor. Um, and I think a lot of people who are kind of reconnecting, and I would include myself in that, even though my process started in the 90s, just kind of like having my grandmother talk about Harris Neck for the first time in my life.

life, like we would go there and she would say we're going to the country and that was about it. And it wasn't until, you know, I was adult, an adult, a young adult in the nineties that she started to talk about it. Can you tell me, um, for folks who are looking to reconnect, what is the best way to do it?

What kinds of programs or what kinds of, uh, guidance or information does the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor offer for that?

Griffin Lotson: Uh, yes. I'm very proud to say I've, uh, wow. I've worked with it. And some of the other names that you mentioned, like Mr. Wilson Moran and so many others. Uh, we were a part of the Gullah Geechee culture.

Um, before it was cool. We'll say it that way. We go way back because we were birthed into it. Uh, but when they were trying to plan it in the early 2000s, uh, when they just had the thought of trying to put it together, wasn't even offered for legislation purpose yet. Through Congressman Clyburn, we were involved.

So I go back to the, um, the real, real history of that quarter in its infancy, late nineties. I think when the idea was thought of. So yes, I've been involved in that. And what, what it does now is all those groups, all those Gullah Geechee, I should say within the quarter, which start in the, uh, Pinto County, uh, which is in North Carolina all the way down to ST John's County in Florida, that 30 miles inland and, uh, Most people don't know.

It kind of mimics that what if people talk about the 40 acres in a mule, which is Field order 15, which was conducted right there from the government after the Civil War and land all of the islands, all of them, the sea islands, you name them, we had on them all. Hilton Head, Jekyll Island, Sin Simon Island, all of the islands, we owned it all.

Sapelo Island, all of it we owned. All of the Harris Neck area was owned by the Gullah Geechee slash African American, but then Lincoln died and the new president converted it back to the plantation owners. So, since that time, all those individuals that still live in the area and have traveled to the four corners of this earth now.

So Gullah Geechees just don't live within the quarter because we have children and grandchildren and many of them were traded to various plantations outside of the four states. Most people don't, uh, give that recognition. So those traditions and the way we talk, come Yuh dis yuh dat day, and all of those things.

Came into play all over America and on foreign soils because slavery was still going on. But today, 21st century, what it does now, there's a lot of festivals. There's a lot of individuals that's within the Gullah Geechee culture, the basket weavers, the ring shouters. Uh, the corridor itself has been a Mecca for information.

Now we're beginning to give some seed money. Uh, to, uh, these organizations so that when they once had a little festival, they might've had 25 to 45 people to show up. I've lived long enough to see to the point now that thousands show up. That does my heart good to see when it grows from zero. Now it is known, uh, many parts of America and the world.

We still have a long ways to go, but being that I'm on the commission, I get an opportunity to talk with people like Mr. Gates. I get an opportunity to work with film production, uh, like the movie Roots. I had a major, uh, part in that movie, not just a tiny piece, a major part, which came from our culture dealing with the ring shout.

Uh, Oprah Winfrey, uh, Queen Sugar did some writing for them from Our culture, one of the songs they wanted to use in many other people. That's a part of the culture. I've got opportunities now that was never, ever thought of. Uh, but because of the Gullah Geechee commission, it has went to a higher level. And I still say we haven't scratched the surface yet.

I think it's a long way to go, but I'm very grateful since 2006. And we're close to, uh, 2026. Uh, it has grown tremendously and I hope we continue to see success in that area to help. Those individuals that want to keep their culture alive. Thank you.

Michelle McCrary: I appreciate that. And you brought up two things, actually three things I want to talk about.

One, I know you also manage the Gullah Geechee ring shouters. That's one thing. And then another piece of that, as you mentioned, all your work kind of being a consultant for a different, you know, Films, um, TV, uh, about the culture. You were one of the people who was responsible for uncovering the true meaning of the song Kumbaya.

And I would love for you to talk about the ring shouters and also, um, about Kumbaya

Griffin Lotson: again, that's another two hours. I love doing these things and what happened is, and you'll find this out when you talk to some of you. Other individuals you're going to be interviewing Rutherford and Wilson and Moran and others.

Uh, we actually love what we do. We don't do it for the money, uh, but because of our expertise, sometimes people are willing to fly us to different places. I've went to, uh, Central Africa, Congo by invitation. Can you believe that? And, uh, in the midst of Uh, the coronavirus. So I guess I'm a little crazy, too.

You know, we love the culture so much that we do things that normal or most people don't do. I won't tell people that that that climb Mount Everest that they're not normal, but I have zero interest in trying to climb Mount Everest. But I say it in this contents. For me, the Mount Everest is Sharing what I have learned and learning from my travels and talking to people that are older than I am, and sometime younger, I've traveled the length of this earth for the Kumbaya.

I was in Dubai doing interviews. I was in Germany with some German friends of mine that filmed us locally at my local church, uh, in Darien, Georgia, Sam's Memorial Church of God in Christ. And they were from Germany. Years later, I went to Germany to film them because of the kumbaya. They were taught this in Germany from a book that's called The Trumpet.

And, uh, I could not believe it because the same sound kumbaya, which I'll give a little bit now, which derived from the Galageti culture, we did extensive research for about a decade, and they were being taught it in Germany. And we were not being taught it in America. I just thought that was fascinating to me.

So we traveled there to talk with them in, in different, uh, Seoul, Korea, just interviewing individuals. Have you ever heard of the song Kumbaya? Oh yeah. Kumbaya, Kumbaya, Kumbaya. China, uh, everywhere who don't know that song or that phrase, which a billion people know, what the public did not know is that.

The first known recording in the world was done within the Gullah Geechee culture, put your seatbelts on, in a little town called Darien, Georgia. I certainly didn't know it. Uh, the world didn't know it. So I dedicated my life, I had a great mentor, uh, which is, I never met this mentor, but I feel like I know him, which is Lorenzo Dow Turner.

Uh, they call him the godfather of linguistics in the African American culture because he's African American. He took 20 years of his life traveling here in America within the Gullah Geechee culture and in Africa. So I had a great mentor. If he can dedicate that much time in his life, I can dedicate some time.

So my claim to fame is Georgia has its first historical song, which is Kumbaya. Now, Uh, the Library of Congress and Congress has recognized this particular song that's coming from the Gullah Geechee culture. We had to work hard and, uh, we made it happen. Of course, not by myself. I used the legislators and other individuals and we pushed, we pushed, we pushed.

And now the first book in the world has been written on my research. Uh, because when my days are all over and I go to be with the ancestors, I want this knowledge to be here on planet Earth for another individual can pick up where I left it off and perhaps find some more information concerning that same kumbaya.

Thank you.

Michelle McCrary: Can you translate that for folks? Cause people say kumbaya. But it's Kambaya, I am, and my pronunciation is probably even off, but can you just translate for folks that may not know what that means?

Griffin Lotson: Yes, I'm going to give you three versions of what it is. The most famous version, which was, um, famously recorded, Joan Baez, she's still alive.

Peter Sagal and many others. Even B. B. King did a version of it, I guess, because it was so popular. He wanted to get in on it, make some money too, but he did a version of it. And we all know now thousands and thousands of groups sing that sound. The most famous, and I'm going to give it in order down to what the, uh, Enslaved and the Gullah Geechee The most famous version is Kumbaya.

Now I explain it since we have a little bit of time and let me know when I'm talking too long, but the Kumbaya by those famous singers, most people don't know they went to the Library of Congress with their professionals. They're looking for new material. And for whatever reason, they go and research and look, and they found some of these songs.

They did not know they were going to be famous. Uh, they just sung it and it took off like a rocket and I say that about the ring shouters and we'll give some more about that later. We did the same thing for about Eight to ten years, the same script, kind of like a politician, they say the same thing. So we say the same thing about the dialect.

And we would say the dialect, and while we, one would interpret it in English, and then we would say the dialect side of it in, in the, uh, in the, uh, in the, in the way that we talk. Come y'all this y'all that day, and somebody would explain it, uh, on the English side. Come here, this here, that over there. We would explain it.

And it took off. We didn't know it was going to take off. We've hoping to get 50, 000 hits or 25, 000. The last count that we had, it went over 3 million. Nobody in the Gullah Geechee culture ever gotten 3 million hits that went viral, but we did same thing with the, uh, Kumbaya, uh, those famous singers sung the song and it just, everybody was buying it.

So that's the most famous, which everybody know Kumbaya. They thought it was recorded in Africa. Uh, that's where they were singing it. No, some missionaries took it to Africa, and then the Africans started saying it in their patois, kumbaya, which the next most famous words before it was, uh, kumbaya, the most famous one before that was in the hymn books.

And this is what the missionary took, which is come by here. And in the sixties, that same sound, come by here, was in the civil rights movement. And they sing, come by here my lord, come by here, and the rest of the verses. Now, I saved the best for last. And remember this, all those that will be listening to your podcast, the original word was not kumbaya, and it was not come by here.

It was come by ya. If my parents were calling me. They'll say, Hey, Griff, come. Yeah, boy, come. Yeah, we would use the word. Yeah, we would not use the word here. And then the Gullah dialect when the recording the first known recording. I got my hands on it because they said this guy has a little bit of knowledge.

I used to pay for material at the Library of Congress. Once they saw I had a little bit of knowledge. I didn't have to pay for anything after that. They gave me the material. Because I was of the Gullah culture in closing with that same Kumbaya, but the original words that come by. Yeah, I listened to it.

And the hair stood up on my arms. I had purchased a house that was owned by a former slave, Ma Jane, that's in the drums and shadows. And I purposely said, I want to listen to it with my earphones on, and I placed it on the bed. I recorded all of this because I didn't know what I was going to experience, but I thought I was going to experience something great.

And I did.

Michelle McCrary: Thank you so much for listening to Curious Roots. Learn more about Harris Neck at HarrisNeckWantTrust. org. and find out more about their work with the African American Redress Network at redressnetwork. org. Learn more about Black coastal communities from North Carolina to Florida at gullahgeechecorridor.org. You can support Gullah Geechee communities on St. Helena and Sapelo Islands by following ProtectStHelena at ProtectStHelena. com and SavingOurLegacyOurselfSolo at SavingOurLegacyOurself. org All links are in our show notes. Thank you to my relatives who are now with the ancestors, Miss Mary Moran, Cousin Evelyn Greer, Cousin Bob Thorpe, Cousin Chester Dunham, my father, Rodney Clark, my grandfather, Rufus White, and my grandmother, Margaret Baisden White.

Season two of Curious Roots is produced by Moonshadow Productions and with the generous support of Converge Collaborative. Thank you so much for listening.

Season Two

Episode 4: This Why We Come To Be Kin

We continue our conversation with Adolphus Armstrong of the Lowcountry DNA Project in this episode. We return once again to the issues of land, removal, heirs property, and exploited labor as those topics relate to Harris Neck and beyond. We also talk about the book The Half Has Never Been Told : Slavery And The Making Of American Capitalism by Edward E. Baptist and how the patterns of enslavers trafficking stolen African people across the country are seared into the DNA of Black folks today.

(Image: My 3rd great grandmother Ethel “Effie” Proctor (neè Thorpe)

-

Archival Audio

Margaret Baisden White: Testing. Testing. November 8th, 2002.

Robert Thorpe: Okay. Now, where I said we are, we are really close from the Thorpes, Because you know, your, your grandma Effie was a Thorpe.

Margaret Baisden White: She was?

Robert Thorpe: That's what I said.

Margaret Baisden White: See I didn't get any information.

Robert Thorpe: Okay. Umm, um, oh, anyhow this is why we come to be kin! Eddie Thorpe, old man Eddie Thorpe.

Margaret Baisden White: Yeah, I heard of that.

Robert Thorpe: That's his daughter.

Margaret Baisden White: Oh I didn't know that.

Robert Thorpe: Van.

Margaret Baisden White: Yeah?

Robert Thorpe: and Eddie.

Margaret Baisden White: Those two? But I know……

Michelle McCrary: Welcome to Curious Roots. This is Michelle McCrary and before we jump into the second part of my interview with Adolphus Armstrong from the Low Country DNA Project and Ujima Genealogy, I just want to tell you a little bit more about the voices that you heard at the top of this episode. What you heard is a recording my grandmother made with her cousin the late Bob Thorpe. In this moment, he is revealing to her that her great grandmother Ethel “Effie” Proctor is not a Proctor, but a Thorpe and that she is the daughter of Old Man Eddie Thorpe and Van. Now I am still trying to piece together the trail that leads me back to this information that Cousin Bob revealed to my grandmother.

I have some inklings, I have some suspicions, I have some working theories, but what I can say is that this connection is not only on our family tree but also in the family DNA. So I will, of course, keep you posted on what I find out about, um, Ethel “Effie” Proctor's true parentage. I am hoping to gather more information over the coming weeks.

I'm pouring over census records. I'm picking the brains of my relatives and elders to figure out how Old Man Thorpe and Van got together, what was happening with the family at that time, um, you know, where they were living, all those things. So I'm hoping to share everything that I find in my kind of like detective journey with you, um, on the website, CuriousRootsPod. com and if I get it together, I'll post some things on Instagram at Curious Roots Pod. Please don't forget to rate, review and subscribe to Curious Roots on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and iHeart Radio and wherever else you get your podcast goodness. Um, all those things really help and I would love to get some feedback from you all.

What do you want to hear more of? Um, do you have your own stories that you want to share? All that stuff would be really cool to hear. Um, if you don't have social media or anything like that, you can also email me at curious at curious roots pod. com. Please, please enjoy the second half of my interview with Adolphus Armstrong.

And again, so much for listening.

Adolphus Armstrong: And, and the one thing I want to stress to your listening audience is that this is something that is unique. To our people keep in mind to kind of put this in perspective is that while we were denied 40 acres and a mule at the same time, our government, the United, the government of the United States of America were using the homestead acts was granting 160 acre land grants in the West and Midwest at the same time. So in terms of what our connection to the land is that, again, if individuals coming, you know, European passage recumbent United States are being granted 160 acres. And they have not contributed anything to the foundation, the wealth and economic well being of the United States of America.

Kind of gives you an idea as to, you know, what our people, our ancestors have contributed. Because one of the things, an example that I always use is that I grew up on that coast of Georgia. You're driving from, Between Darien and Brunswick. And between Darien and Brunswick, you know, you're going over Butler Island.

And you look to the left, you look to the right, and you notice you see these straight lines, where those rice fields, rice paddies used to be. And you know, there is not, nature does not move in straight lines, and so when you look out, And I'm literally getting a chill just recalling the first time the thought hit me is that you have to think in your mind's eye is that our ancestors created those straight lines that we still see in nature today.